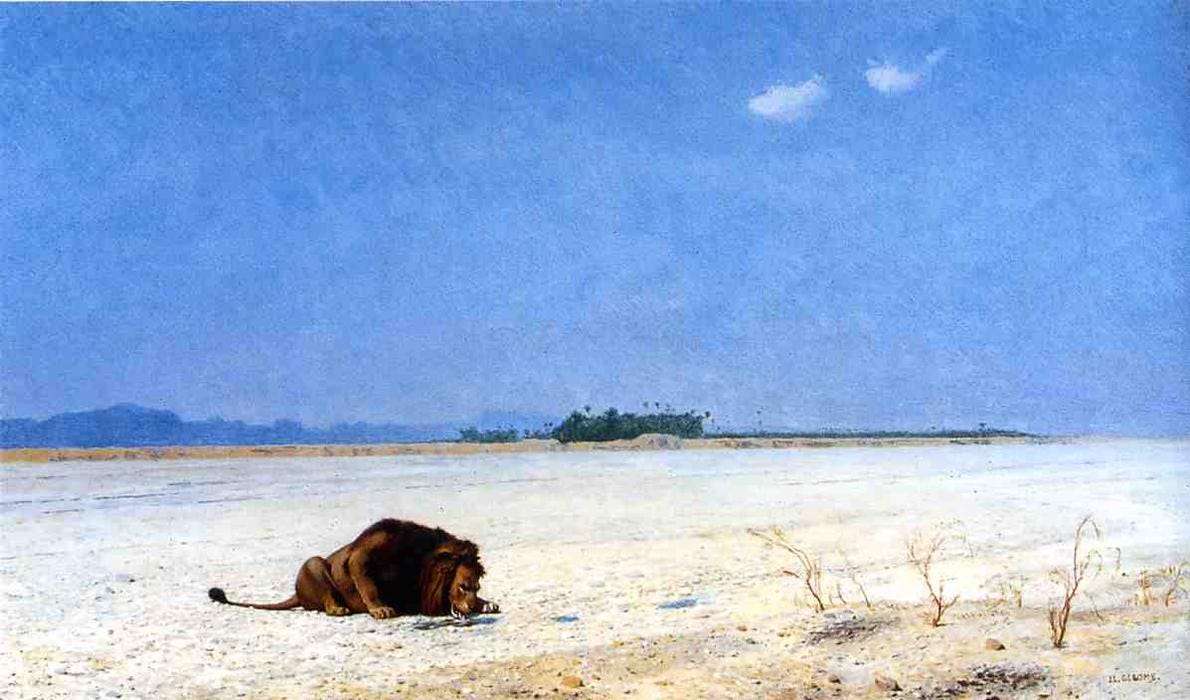

“The lion roars at the enraging desert,” wrote Wallace Stevens […] The more our desert the more we must rage, which rage is love. The passions of the soul make the desert habitable. One inhabits, not a cave of rock, but the heart within the lion.

– James Hillman, The Thought of the Heart

§ Flytrap

I joined Substack reluctantly. The decision felt, at the time, like a concession. I was trading in my beloved stationary — fountain pen, stamps, and envelopes — for a digital platform that “provides publishing, payment, analytics, and design infrastructure to support subscription newsletters.” I was selling my horse and buggy for a brand new Ford Bronco.

The young Luddite was growing up. My suspicion of algorithms, my opposition to the attention economy, my withdrawal from the myth of progress — these idealisms were burning off my personality like corn husks on a grill. Growing up, in this sense, is a despondent affair. It simply means no longer having, as Benjamin Martin put it, “the luxury of principles.” But perhaps my idealisms were naïve. Perhaps I was not abandoning principles, per se — or learning to love the bomb — but was, in fact, emerging from an adolescent rebellion. Perhaps my worldview was becoming more nuanced, complex, more capable of holding contradiction. I still don’t know.

For the time being, Substack is a refreshing alternative to social media whose profit is generated primarily through ad-revenue. But upon joining Substack, it didn’t take long to notice similar trends here — clickbait, thirst traps, listicles, now video reels — and, more broadly, forms of writing optimized to capture attention.

The platform itself promotes these trends, reminding you, constantly, of what kind of content and branding are optimal for growing one’s audience. In doing this, Substack produces a gravitational pull on our collective attention. And so, naturally, our writing pools in the low places. Writing that was not meant to be chewed on, but rather to go down easy. Writing with SUDDEN SHIFTS IN FONT AND STYLE to keep your tik-tok-rotted-mind from getting bored. Writing that’s sweet and sticky and made for fruit flies.

In a sense, these dynamics are as old as writing itself. It was always a game of attention and salience, and everyone — whether reading or writing — has her part to play. I’ve certainly played mine. I was, as I said, reluctant to join Substack. But then I’m reluctant to join anything; I tend to live on the margins — begrudging the tide I’ve been swept up in. This role is old as time, too. On this platform, I’ve limited my participation to making tiny quilts with abstruse symbols, then draping them on fenceposts at the outskirts of town. Maybe you’ll walk by one of them and find it beautiful, and I’ll feel somewhat smug.

Maybe there’s no problem at all, nothing to see here — just the spiral of human history. Perhaps it’s just me, at the edge of town, announcing my resentment and cynical distance to passersby who never asked.

§ Flytrap2.ai

But there’s a new sheriff in town.

Recently I discovered how common it is for people to use A.I. chatbots, like Claude.ai, to co-author their essays on Substack. Very common. It was only a matter of time.

A recent essay by Daniel Thorson is an explicit promotion of machine-assisted thinking and writing. Another, by Jane Weintraub, proposes a conceptual category for this emergent form of cyborg thought: nexalism. Both make the claim that A.I. chatbots like Claude.ai can help us attune to our innate embodied knowledge, giving us words that resonate with our tip-of-the-tongue insights.1 They can help us articulate, Thorson insists, what we already know.

This kind of thinking — formulated, presumably, with the aid of Claude.ai — reveals the extent to which we have entered a post-literate age. A.I. chatbots are helping us justify, to ourselves and others, our own use of A.I. And it represents a radical acceleration of the attention-capture dynamics already at play on platforms like Substack. This watering hole is about to get a lot more sticky. Not long from now, we won’t have to be concerned about shifting our tune to keep our audience engaged; the tune will no longer be ours to shift. The last bastions of the written word will be filled with text not written, but generated by conversations had between increasingly complex beings and their increasingly domesticated pets.2

Perhaps this slip-and-slide into an era when no one really writes and no one really reads is inevitable — ORALITY IS BACK, BABY! — but so long as the memory of writing as a creative act is still alive, I want to stand for language and thought as non-mechanical phenomena. So for anyone feeling the seduction of artificial intelligence, I’d like to ask a few questions. What happens when we let algorithms shape the way we write, or let chatbots in on our creative process? What is being outsourced here?

Two answers come to mind: style and imagination.

Style is how something is said. It shows through tone, texture, intent. Style is the soul of language — her corduroy pants. Imagination, on the other hand, is both what creates style and that which perceives the necessity of any given style. In the preface to Lyric Philosophy, Jan Zwicky highlights what I’m getting at here.

Why are there different genres of linguistic communication? Why are there both prose fictions and epic narrative poems? Both hymns and theological discourses? Love letters and marriage contracts? I believe the answer is because how we say is fundamental to what we mean.

If it’s true that how we say is fundamental to what we mean, then style is an essential component of linguistic meaning. Just imagine how it would feel to read Zwicky’s final sentence — her core conceptual insight — without the questions preceding it; without the juxtaposed genres, the repetition, or italics. Consider how vital these stylistic elements were for you to truly grasp her thought.

Style, just like genre, is not incidental or ornamental. Some insights can only be conveyed, in language, through poems. Some want to become essays; others, aphorisms. And to discern which genres and styles are appropriate for any given insight is a function of the imagination. In other words, imagination is a bridge between the unsayable and the sayable. It helps us cross the gap between lyric perception and syntactic consequence.3 The imagination translates insight by bending language into its proper shape. But when the form is prefabricated — offered to you rather than emerging through you — the process of grappling with the shape of the insight is largely outsourced.

A contractor builds the dream house of five separate families; so why are all of them McMansions? Outsourcing the process of articulating our insights, I believe, does not respect their form. Why? Because style is the trace of the insight, the imprint of its shape on language. If the dream house always takes the form of a McMansion, it means the shape dream itself was never really felt. It means something else is imagining our lives.

To be clear, what happens when we fall prey to algorithmic incentives or are seduced by the creative bypass of A.I. is not, I think, an absence of style. You cannot separate content and form: this is a deep ecological fact. But style can become unconscious. We can forget about it. And when we do, we live out dreams that aren’t really ours. Our writing starts to say things that we don’t know we mean. Its content might insist on the importance of “slowing down” while its style has no syntactical variation — no bumps or texture to create resistance — and instead lets your mind slide away on a frictionless sheet of ice. It’s content might oppose the notion of technocratic attunement while it’s form — clarified by Claude.ai — provides highly consumable conceptual frameworks in bullet-point form.

The implicit meta-message of such writing is that writing is essentially information. A bodiless spirit.4

But writing can still have blood in it. Writing comes from fingers, after all, and a furrowed brow, from pacing back and forth for hours. Writing comes from language — that flower patch of the mind — which in turn comes from song and dance and death. When language and thought are outsourced to an artificial intelligence, rather than wrestling with the endless paradoxes that language creates, then the trace of that wrestling is gone. The style says: there is no struggle. But there is a struggle. Writing is a struggle, and ought to be.

§ Desertion

I’m angry. And I’m grateful to James Hillman for giving language and image to this impersonal anger: “The more our desert the more we must rage, which rage is love.”

As we welcome the desert into our most intimate places, I’m reminded of Kant’s aphorism about the dove. Flying freely, the dove feels the resistance of the air beneath her wings. She might, Kant says, “imagine that she would fly even better in the void.”5

I know, personally, that the seduction of product without process is very hard to resist. Especially now. Process is a mess; creativity, a battle. Learning to think is hard. Not to mention inefficient. Who has the time? The air beneath your wings is labour and loss, bewilderment, confusion, and limit. What would make this even better? What would make this easier?

Owen Barfield once wrote: “Perception comes to us; but we have to do thought.”

But now, of course, the spiral of human history — which seems to be screwing itself — has proven Barfield wrong. We don’t have to do thought. But we should discern, for ourselves, what thought really is. When a chatbot helps you articulate something — that insight on the tip of your tongue — is it telling something you already knew? Or is trying and failing to articulate that insight yourself, the process of coming to know, part of the knowledge itself?

I once asked Tim Lilburn about the nature of style in writing. He responded: “Personality goes very deep. So style goes deep.” When style becomes unconscious to us, our imagination withers, and our writing no longer becomes an expression of our personality. It becomes an expression of something else.

I want to know you. I want to hear your voice, not an echo of a conversation you had with nobody. It can take years to find your voice. And it should. Because human beings, like it or not, are made.

I won’t address Thorson’s article in great detail here, but I want to use it as an example for a much broader relationship to writing, technology, and to our conception of knowledge itself.

I’m quite aware that there are multiple voices in this essay. This voice is a rather sensationalist, McLuhan-esque techno-pessimist. I trust he has gifts to offer as well as blindspots. What matters, to me, is not the coherence of all the voices here, but that they’re all mine.

The point Thorson is making in his recent essay is that A.I. can help with this translation — likening it to Gendlin’s notion of “crossing” felt sense experience to conceptual frameworks. Something in my felt sense tells me it’s much more complicated than that. I can’t quite put my finger on it. How should I relate to this hunch?

Language, especially written language, already has a tendency to producing disembedded, disembodied thought. Using A.I. to help you articulate your thoughts enshrines this tendency. It amplifies a sharp duality that can, through crafted language, be troubled.

I found this translation of Immanuel Kant’s thought, which appears in The Critique of Pure Reason, in Simone Weil’s Gravity & Grace — which was, in turn, translated by Arthur Wills. I like their language more than the usual translations of Kant’s sentence.

This was such a delight to read. Thank you so much.

Favorite bits that make me laugh and recognize you, the person that I love:

"these idealisms were burning off my personality like corn husks on a grill"

"I was, as I said, reluctant to join Substack. But then I’m reluctant to join _anything_;"

"On this platform, I’ve limited my participation to making tiny quilts with abstruse symbols, then draping them on fenceposts at the outskirts of town. Maybe you’ll walk by one of them and find it beautiful, and I’ll feel somewhat smug."

Thank you for being you, and laboring to bring this voice into language; it's a joy