for Sylvan

§ I

Gloria Patri, et Filio,

et Spiritui Sancto,

Sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper,

et in sæcula sæculorum.

Amen.

§ II

A week before the cold snap, I visited an old friend in Vancouver. It was warm outside for January, a warmth we enjoyed as we walk to the market together. Low winter light glanced off the puddles on the street. Cherry blossoms were blooming a pink and white belief in a false spring.

A few hours earlier, we were sitting in the kitchen waiting for the water to boil. Roommates murmured through the house, sleep lifting like fog from a vineyard. My friend was sitting across the table. His hair had grown out since I saw him last. Now, he tucks a wavy black lock behind his ear. Now, his father is dying. Now, he pours boiling water over coffee grounds and recounts his dream from the night before. We moved seamlessly into an apocalyptic landscape, just me and an old man whose face I never saw. We scavenge in empty shopping malls, glean from fallow fields, and walk along highways full of cars abandoned like crab shells. Everything is tempered by necessity. Conversations don’t just kill time, they provide as much heat as fire — all the things we never knew we needed. And there is pleasure in this simplicity, pleasure in the puzzle of staying alive. We meet others along the way who are struggling. We give them some of our meat. We talk to them, me and the old man, whose face I never saw. He passed me a cup of coffee.

I didn’t broach Jay’s illness directly. For most of the morning, we let our conversation meander. How do you talk about something that is everywhere?

On our walk to the market, we talked about Tarkovsky. My friend had just watched Stalker again, this time on the big screen, and was still reeling. It had been a while since I’d seen the film, and I was out of my depth. Reaching for something to contribute, I recalled the last scene of the film — the only one I remembered clearly — in which the daughter moves a cup across the table with her mind. But my friend, an artist like his father, was far more impressed by a scene just moments before: the daughter’s golden tassled shawl, her downcast eyes, the desolate snowy landscape gliding by her profile, and something, something strange about how she’s walking. And then, as the camera zooms out and pans, what was strange becomes, miraculously, understood. “That scene,” my friend told me, “demonstrates Tarkovsky’s mastery of his medium. He could reveal truths only possible to reveal through film.”

I had remembered the daughter’s miracle; my friend had remembered Tarkovsky’s. But they are, it occurs to me now — now that it’s so cold outside — different kinds of miracles. The daughter’s telekinesis cannot be explained, at least scientifically, which is what makes it miraculous. But Tarkovsky’s is itself a kind of explanation: a revelation.

§ III

There is an essay I love called “Lenses.” In it, Annie Dillard recalls her childhood habit of watching drops of pond water evaporate through a microscope. She’d rigged a 75-watt bulb to the contraption, which quickly heated and dried up anything she placed on the clear glass slides. As the drops of pond water condensed, the translucent critters within it would start to squirm and eventually die off as the water turned to vapour.

I was, then, not only watching the much vaunted wonders in a drop of pond water; I was also, with mingled sadism and sympathy, setting up a limitless series of apocalypses. I set up and staged hundreds of ends-of-the-world and watched, enthralled, as they played themselves out.

Recently, after returning to her essay, I looked up the word “apocalypse” in my Oxford English Dictionary — the condensed version — which is, by far, the largest book I own. To my surprise, I found no mention of worlds-ending catastrophe. It’s an old dictionary, published around the time Annie was playing God with her microscope, which might account for the absence of its now colloquial meaning. In any case, the dictionary informed me that the word “apocalypse,” in its ancient sense, means revelation, to reveal.

By the end of “Lenses,” the core elements of the essay have changed state. Annie grows up and becomes mortal, and the drops of pond water become a pond.

§ IV

I got home from Vancouver just as the cold descended. I stayed inside all day. Outside, and across the province, temperatures had dropped to record lows. Ice clung to the windows, and the wind tormented my building like a snapped towel. One local news outlet, playing tag with the weather’s hyperbole, called it an “arctic intrusion.” Next year, I reckon, it will be an invasion. It is true that the North rarely winters this far South, but did we not, in a sense, welcome it? How long before these patterns become gods again, before the people shake in their tents, repent, and find themselves believing?

The daylight was low and thin. I looked up from my book and saw the clouds turning lavender. It was enough beauty to compel me to go outside, so I buttoned up my coat, quit the building, and walked to the sea before it got dark. The beach had cleared like a parking lot. Only the driftwood logs remained. I did not notice the sand or the waves or the islands off the coast, or anything other than the wind and its needles million. I tried to walk the length of the beach, felt determined to do so, but the bite on my brow was too painful and turned me around.

With my back to the wind, I could see again. That’s when I noticed the foam. It huddled in strips running parallel to the tide line, and a few meters above it. The tide had gone out hours ago, but the foam stuck around. How had it survived? The wind had swept away almost everything, including the humans, off the beach, and of all that had vanished, it was the foam that remained. I approached a streak of it slowly — as one would a ghost — and prodded it with my toe. It crunched. The foam, the sea’s frothy edge, ephemera, had frozen.

Prodding at the frozen sea foam, I thought about Tarkovsky. How he had mastered his medium — found ways to reveal truths that only film could tell. Staring at the foam, I felt the world revealing itself, what it can do and become, revealing its edges and endless transformations. This seemed, to me, miraculous. As if the world itself were a film, some kind of medium I had never noticed before.

Who, then, is the artist?

§ V

Pierre Teihard de Chardin, a paleantologist and Jesuit priest, a man who, one hundred years ago, unearthed ancient hominid skulls in the Gobi Desert, once wrote: “If I should lose all faith in God, I think that I should continue to believe invincibly in the world.” A peculiar thought. After all, must one really believe in the world?

A few months ago, when the city was covered in snow, I saw an old woman shuffling, unsure of her footing, on the sidewalk. Although I considered it, I did not offer her my hand.

§ VI

A few days after I saw the foam unclasp itself from the sea, I had another strange encounter. I was on a walk in the meadow when I came across a frozen puddle. It had pooled right across the trail I was walking, and there was no easy way around. So, I stepped onto the ice, timid as a foal, expecting it to crack under my weight. I recalled Peter’s first steps on the sea.

But the puddle had frozen solid. I looked down and saw, to my astonishment, a forest of tiny grasses an inch beneath my feet. I crouched to get a closer look. Above the grasses, trapped within the ice, were little beads of air streaming upward. Together, the little beads formed a kind of cloud, like a fog draped over a vineyard. It was, I realized, the first time I’d ever seen photosynthesis. And as I marvelled at these little breathing beings, my wonder turned to horror. I imagined that the blades of grass had cried out, already drowning, bubbles streaming from their mouths, as the aquatic world around them stiffened, expanding and cracking, thicker, everything thicker and slower, time slowing down; and the invisible, the air you breath, becomes a fog you can see, and the song you’ve been singing all along goes utterly silent, trapped, going nowhere until time starts again.

Are these revelations, these apocalypses, happening all the time?

Perhaps life always appears like this, avails itself at the very limit. On our walk to the market, my friend imagined that his father might not reckon with death until his last moments. Is death cold? Is that why it makes life, like a winter breath, visible?

Are we trapped beneath the microscope of a girl who’s now discovered liquid nitrogen? Does she watch us looking around uneasily as the conditions start to change — the foam freezing, the air catching fire — until we start to shout for mercy?

§ VII

These days, we rest assured that god is dead — especially god the Father. The void he left was frightening at first, but we’re used to it now. And the miracles of the world that science revealed, and then explained, no longer have the power to astonish. Now science, too, has become a bit passé.

Where will the world go when we no longer believe in it? Where did the Father go when he died?

§ VIII

I was walking through a courtyard, surrounded by brick buildings, when I saw Jay. He was busy at a garden plot, planting his tomatoes, and talking away on the phone. I didn’t want to disturb him or interrupt his call, so I walked around the garden and placed a hand on his shoulder — thinking we’d acknowledge each other silently. But when he saw me he burst out of himself, elated, to greet me. He seemed to forget entirely about the phone call. I didn’t. As we chatted, I felt tethered to the person on the other end of the line, who was now, I imagined, listening in on our conversation. He had more energy, and hair, than when I’d seen him last. And based on his features, I tried to calculate when this moment in the courtyard — which never happened, or maybe only happened now — might have been. Jay makes a comment about death, about beating it somehow. I smile and think of cherry blossoms, a false spring. Then I ask him a question. And just as he’s about to respond, his son, my old friend, enters the scene. Jay turns to him, once again ecstatic, and they enter into a frantic exchange over a minor logistical detail: what time he’ll be picked up to go to the barber shop; if the barber shop is even open today. Do we really need to drive? Do I really need a haircut? I stand there and wait for the conversation to end, for Jay to come back and answer my question. I wait there, I realize, just like the person on the other end of the phone call. Finally, Jay turns to me and looks at his watch, and I know I’m not getting an answer. Time is up. Jay gives me a wry smile, as if he knew the whole time: that this was our goodbye, and his apocalypse. That he died six days ago and hasn’t had a moment’s rest since. That he must be on his way.

§ IX

On our walk to the market, we talked about Tarkovsky. It was warm outside for January. Cherry blossoms were blooming a pink and white belief in a false spring.

Eventually, when the time was right, the conversation arrived at Jay. My friend told me that the shock of diagnosis had worn off. Now I could probably talk about it with a smile on my face, he said. But I could see his face. Jay’s illness was everywhere. Not in his eyes so much as what they seemed to see. Not in his words so much as in the air they emptied into air. How can you talk about something that is everywhere?

Everything had changed for him. The world was stranger. The film between realms, thinner. Just a few hours ago, he said, I was a scavenger, roaming through an apocalyptic landscape with an old man. Now — he sweeps his hand across Vancouver’s skyline — I’m here with you, and the world seems put-together again. But he was not living in a new world, the world of dreams and ghosts and dying fathers. That world is this one. He was here, painfully here, in the way it always was. It is like this with grace: everything changes because nothing needs to.

§ X

A miracle is an apocalypse. A revelation, not a magical intervention. The end of the world as you knew it.

When I got home from Vancouver, I decided to watch Stalker again. After almost three hours of psychedelic wandering, I arrived at the moment my friend had spoken about. There, on the screen, was the close-up of the daughter’s profile, her head covered in a golden shawl, her downcast eyes, solemn — as though she were in a funeral procession — the sound of heavy footsteps on wet gravel and mud. A desolate landscape drifts behind her as would a dream. The camera zooms out, pans right, and for a moment, as the daughter’s torso enters the frame, her body appears strangely stiff. Too upright and rigid for her to be walking normally.

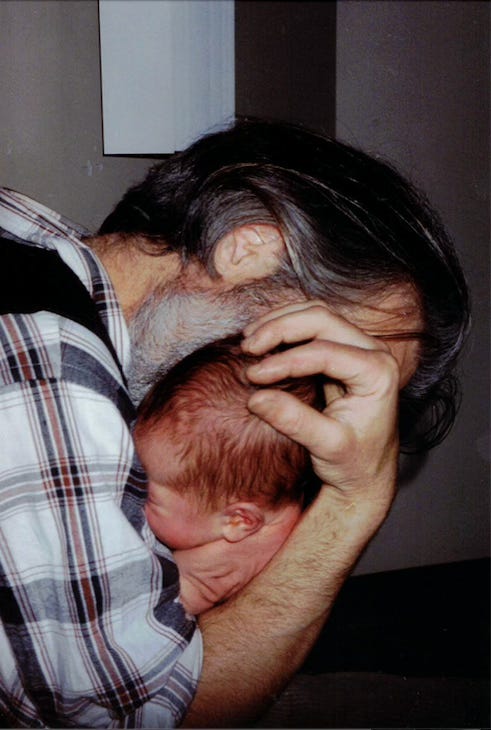

Then it happens. You realize she’s not walking at all. As the frame opens out, it reveals another person: the father is carrying her on his shoulders. He walks toward a frozen lake.

Every creative act — be it directing a play or fathering a son — is an act of self-portraiture. And in this scene, palpably so. As if Tarkovsky snuck into his own film, just as the unconscious represents itself, in dreams, as water. You never see his face, the father. But he was there the whole time, just outside the frame. And still is. He’s the one behind the camera, the world without end, forever holding you.